Cottonopolis: Lessons for environmental science through the lens of Manchester

This AHRC/NERC-funded project explores the archives of ‘cotton’ to unsettle the celebration of Manchester’s history as a city of science and innovation

The project also challenges us to rethink the history of environmental knowledge production at The University of Manchester and our role in Manchester’s colonial legacy, revealing our complicity in global socio-environmental legacies.

Overview

Within its much celebrated ‘innovative past’ Manchester – and its industries, private businesses, universities, and cultural institutions such as museums, libraries, art galleries, and observatories – were key hubs in the expansion of the UK’s colonial aspirations.

This project interrogates Manchester’s role as the first industrialising city, and the dominance of the expansion of global cotton markets through environmental science, which ultimately provided the cultural and scientific authority that underpinned colonial expansion, frontier agriculture, and colonial urbanization.

In this project ‘cotton’ is a starting point from which to unsettle the celebration of Manchester’s history as a city of science and innovation, challenging us to rethink the history of the first industrial city as a global socio-environmental history with a problematic legacy for the environmental sciences.

Through the histories of cotton, we reveal the socio-environmental legacies of industrial Manchester and the environmental knowledge and impacts this legacy created.

Using a range of methods from archival research, interdisciplinary and creative arts-science methods, and mapping we explored the following.

- How can research into the hidden histories and archives of cotton, present across the city of Manchester, reveal the trajectories of global environmental and social transformation in the 19th and early 20th century?

- Using the history of cotton in Manchester as an inflection point, what claims can be made on the epistemology (underlying ways of thinking or doing) of environmental science?

- How can scientific, social science, and art-based methods reveal Manchester’s longer-term effects on the use of the land (land use, land cover) across Britain’s empire?

The project culminated in an exhibition and public workshop exploring these themes led by Laura Pottinger, Ali Browne with Natalie Linney (textile artist) and members of the Cottonopolis Collective at Queen Street Mill across September and October 2023 as part of the British Textile Biennial.

Background

Cotton is central in Manchester’s past, and its impacts linger in the spatial, economic, scientific, and industrial configurations of the city.

Diverse academic scholarship has focused on industry, labour, and institutions that are deeply connected to Manchester’s global cotton enterprise (Engels; Fowler 2003).

Early scholarship emphasised Manchester’s innovative capacity, rarely recognising the regions where cotton was produced (Bee 1984; Messinger 1985; Kargon 1977).

Critical and more recent scholarship, while recognising the role that British colonialism played in acquiring cotton, nevertheless presented the history of cotton as confined to the city (Jon 2003; Kalra 2000).

Whether focused on growth industries and markets, working conditions, the response of unions, or how cotton defined the urban built environment of Manchester, the story of the history of cotton is often about making claims on the nature of the city of Manchester and its people.

Current scholarship and the turn to global history have further tied Manchester to a global network of enslavement, especially in the Americas, to grow and keep the prices of raw cotton depressed (Beckert 2014).

The city’s history is thus resolutely global, and its people, scientific institutions, and commercial establishments, the mills that define its landscapes and that propelled it to its position as a city of innovation, had a stake in creating and perpetuating a history of inequity.

The novelty of this project is in rethinking the history of cotton and Manchester as constituting a global environmental history.

This project asks ‘what do the environmental sciences have to do with the industrial revolution and the creation of unequal ecological worlds?’

The Industrial Revolution, so central to the history of Britain, was underpinned by the rise of environmental sciences that allowed for measuring, understanding, and ultimately reshaping vast global lands as cotton-scapes.

Cotton - as European colonists of the Americas realised in the early 18th century - simply did not grow in temperate regions, namely much of the United Kingdom and Western Europe.

Britain’s industrial revolution, much of which was premised on cotton and coal, therefore relied on foreign lands.

As Britain’s colonial empire expanded across the Americas, Asia, Africa, and Australia at the height of the British Empire from the 1850s (Bayly 2004), new lands were colonised for agricultural surplus and to feed Britain’s growing industrial populous.

Scholars have long recognised that economic botany, or the ability to commercially experiment and exploit plants, was at the centre of British colonial history (Drayton 2000; Nesbitt and Cornish 2016).

Yet, little scholarship has focused on the local scientific, industrial, and environmental literature produced in British cities, and their broader entanglements with world ecology and legacies of race, injustice, and exclusion.

Using cotton as a focal point, the project emphasizes the constructed nature of environmental science, asking who was producing ‘science’. Commercial institutions (e.g., Manchester Chamber of Commerce, Cotton Supply Association) were heavily involved in the production of scientific and ecological knowledge around cotton, alongside other environmental histories (soil, water, ecology, botany, etc).

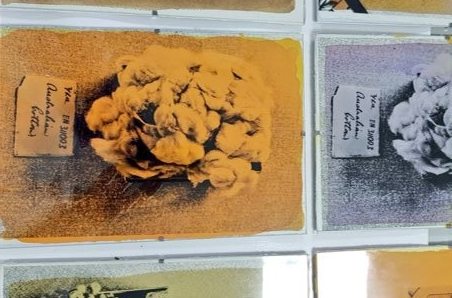

Museums (Manchester Museum) and learned organizations (Manchester Geographical Society; Royal Geographical Society), while claiming neutrality, were part of the British imperial project.

Post 1850s, Britain’s cotton empire in East Africa, South Asia, and Australia were new environmental experiments in new colonial landscapes.

Imperial states employed a variety of environmental sciences to replace local varieties of cotton (Kumta, grown in central India) with a universal (the New Orleans) crop - that Lancashire factories desired.

The development of ecological sciences around cotton fundamentally changed landscapes, waterscapes, soilscapes, and ecologies; and impacted labouring bodies in Manchester and where the crops grew.

Critiques of the past (and developing a history of the present) provide insight into, and a somewhat uncomfortable foundation for, how we might also interrogate current environmental scientific practices.

People

Co-lead by Aditya Ramesh and Alison Browne, with acknowledgment of the initial contribution of Chris Jackson.

Cottonopolis Collective

- Polyanna da Conceição Bispo (co-I)

- Mark Usher (co-I)

- Jenna Ashton (co-I)

- Abi Stone

- Alastair Lomas

- Andy Speak

- Arianna Tozzi

- Aurora Fredriksen

- Chris Jackson

- David Browne

- David Polya

- Dongyang Mi

- Erin Beeston

- Franciska de Vries

- Gareth Clay

- Jenna Ashton

- Johnny Huck

- Kerry Pimlott

- Laura Pottinger

- Laura Richards

- Natalie Zaceck

- Martin Dodge

- Nathaniel Millington

- Rachel Webster

- Richard Bardgett

Funding and acknowledgments

This project was funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) and Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) Hidden Histories of Environmental Science across 2021-2023 with additional financial support from The University of Manchester (Simon Industrial Fellowship – Natalie Linney, Simon Fellowship – Laura Pottinger, Research Collaboration Fund), cotton material kindly donated by Quarry Bank Mill National Trust, and with in-kind support from Manchester Museum, British Textile Biennial and Queen Street Mill Textile Museum.

With acknowledgment of the support from the following organisations and individuals:

- Manchester Museum (Rachel Webster)

- Geography Labs (Dr Tom Bishop, John Moore, Jonathan Yarwood)

- Hayley Caine

- Natalie Linney

- Alistair Lomas

- National Trust/Quarry Bank Mill (with special note to Suzanne Kellett)

- Royal Geographical Society

- Manchester Geography Society

- Joe Smith

- Rachel Kenyon

- British Textile Biennial

- Queen Street Mill Textile Museum

Contact us

Please email alison.browne@manchester.ac.uk and aditya.ramesh@manchester.ac.uk

Find out more

- Aditya Ramesh and Jenna Ashton present on Cottonopolis: Lessons for Environnental Science from Manchester at the Manchester History Festival 2022 (8–12 June 2022)

- Litmus: Environmental Legacies of Cotton at the British Textile Biennial 29 September–29 October 2023 led and curated by Laura Pottinger, and Alison Browne, with textile artist Natalie Linney, and members of the Cottonopolis Collective (including Erin Beeston, Arianna Tozzi, Martin Dodge, Andy Speak, Hayley Caine and Alistair Lomas)

- Cottonopolis turns East: Following the threads of India’s cotton – a photo essay by Arianna Tozzi exploring the socio-environmental legacy of the development of cotton capitalism in Vidarbha, central India

- Cloth Cultures podcast with Amber Butchart in conversation with Cottonopolis Collective researchers Arianna Tozzi and Ali Browne and artist Hendrickje Schimmel (Tenant of Culture)