LITMUS: Environmental legacies of cotton

LITMUS: Environmental Legacies of Cotton is a new exhibition developed for the British Textile Biennial 2023.

Bringing together a series of large-scale textile pieces by artist Natalie Linney with research from The University of Manchester, it aims to unearth and unpick the social and environmental consequences of the North West’s cotton industry.

Led by Dr Laura Pottinger, Prof. Alison Browne, and artist Natalie Linney in collaboration with the Cottonopolis Collective, the work draws on the multiple meanings of a ‘litmus test’ – a universal, dye-based indicator of pH levels derived from lichen, and a social indicator proving success, impact or values.

Drawing on experimental, interdisciplinary research and arts-based workshops, LITMUS: Environmental Legacies of Cotton explores how working collaboratively with cloth, colour, and environmental materials helps to question and reveal the local and global environmental impacts of cotton.

The Cottonopolis Collective and Research at The University of Manchester

As the global epicentre of cotton production in the nineteenth century, Manchester became known as ‘Cottonopolis’.

Though often celebrated as a city of innovation, Manchester’s cotton industry had far-reaching and problematic impacts on people and places globally.

Manchester and towns across Lancashire were key hubs in the expansion of the United Kingdom’s colonial aspirations.

The Cottonopolis Collective, led by Dr Aditya Ramesh and Prof Alison Browne at The University of Manchester, brings together an interdisciplinary team of historians, human and physical geographers, social and environmental scientists, cultural organisations, and artists to interrogate Manchester’s legacies as the first industrialising city.

The research questions the expansion of global cotton markets through environmental science, which ultimately provided the cultural and scientific authority that underpinned colonial expansion, frontier agriculture, and colonial urbanization across the globe.

In this project ‘cotton’ is a starting point from which to unsettle the celebration of Manchester as a city of science and innovation.

By delving into the social and environmental histories of cotton, the Cottonopolis Collective’s research begins to untangle the many ways that industrial Manchester impacted people and environments both near and far, as well as questioning the environmental knowledge it created.

Dr Laura Pottinger is a Research Fellow in Human Geography at the University of Manchester, with an interest in people-plant relationships and everyday forms of social and environmental activism.

Her current project, Making Slow Colour, looks at processes of natural dyeing, and works closely with textile artists, to investigate the relationship between slow, creative practice and environmental care.

Prof. Alison Browne is an environmental geographer at the University of Manchester. She grew up and was educated in Noongar Boodja (Perth/Boorloo, Western Australia).

Since 2010, she has worked in UK higher education leading interdisciplinary projects and teaching about complex relationships between society and environment.

Natalie Linney explores the human connection to landscape, nature & place throughout her work.

Using textiles, form & print, she produces visual responses to current, historical, environmental, and anthropological themes. With a background in eco prints & natural dyes, Natalie utilises ancient dyeing techniques to make site-specific prints documenting landscape and heritage.

Natalie’s practice regularly develops to include new materials & ways of making, she seeks to fuse traditional crafts with modern concepts to preserve these methods whilst making them relevant today.

Creative projects and outputs

LITMUS is a multisensory installation of large-scale textile pieces created by Natalie Linney during an artist residency in Geography at The University of Manchester between April and July 2023.

Linney worked with the Cottonopolis Collective and Geography Laboratories, experimenting with a variety of scientific and artistic techniques on cotton sourced from the National Trust’s Quarry Bank Mill, Cheshire.

Making, Dyeing and Materialising Cottonopolis is an experimental pilot project led by Dr Laura Pottinger at The University of Manchester, bringing together the Cottonopolis Collective researchers with artists Natalie Linney, Hayley Caine, and filmmaker Alastair Lomas in a series of site visits and creative workshops carried out across autumn 2022.

A short film Making, Dyeing and Materialising Cottonopolis: Environmental Legacies of Manchester’s Cotton created by Alastair Lomas documents the project.

The Cottonopolis Anthotype Series was created by artist Hayley Caine in response to experimental techniques trialled in the arts-based Making, Dyeing and Materialising workshops.

Cotton Connections is a cabinet curated by Dr Erin Beeston, University of Manchester, displaying archive material from research undertaken by the Cottonopolis Collective in archives, libraries, and museums across Manchester.

Cottonopolis Turns East: Following the Threads of India’s Cotton by Dr Arianna Tozzi brings together archival material and photography to tell the story of Vidarbha, an agrarian region in central India, and how it was transformed into a cotton-growing hub during British rule.

Photographs on display tell the tale of Lancashire’s continued presence in this landscape.

The exhibition draws on doctoral research carried out at the University of Manchester looking at climate change and processes of agrarian transformation in semi-arid parts of India. (Photographs by Adam Barr).

More information about the exhibit can be found on the Threads page.

LITMUS

Natalie Linney. Soundscape by ZOIR.

LITMUS is a series of large-scale textile pieces created by Natalie Linney during an artist residency at The University of Manchester between April and July 2023, working with the Cottonopolis Collective and Geography Laboratories.

This multisensory installation draws the cotton at the centre of this industry into conversation with impacted soils, water, and plants from sites that were integral to the colonial project of Cottonopolis.

The cloth used for this exhibition was woven on the heritage textile machinery at the National Trust’s Quarry Bank Mill, spun and woven on-site from raw cotton sourced from Louisiana, USA.

To create the installation, lengths of cotton fabric have been buried at sites across Greater Manchester in polluted earth, land belonging to institutions that were critical to the cotton industry or that connects to places globally that have been impacted by Manchester’s cotton science and industry.

Other pieces were suspended and exposed to the elements and pollution on roofs of key institutions and in contaminated rivers.

The unearthed remnants are displayed in the Weaving Shed at Queen Street Mill, Burnley, for the British Textile Biennial 2023.

They are marked by processes of microbial action and industrial contaminants and are pigmented by the earth and plant matter of each specific site.

To explore ideas of repair and reconnection, members of the academic team have begun stitching together the fragmented cloth using cotton sashiko thread that has been dyed with plants.

These include plants gathered at the cotton burial sites (willow and equisetum or ‘horsetail’ from Queensland Road, bracken from Quarry Bank Mill, and weld from Pomona Island).

Threads have also been dyed with edible spices and lentils purchased in India by members of the Cottonopolis Collective Dr Arianna Tozzi and Dr Laura Richards during research visits (turmeric, chilli, garam masala, urad dal and ratanjot or ‘dyer’s alkanet’).

The process of burying and revealing cotton resonates with scientific approaches to determine soil health, and methods associated with the Shirley Institute, a centre for cotton research in Manchester.

By burying strips of cotton fabric, the resulting cellulose decomposition can be assessed to understand the processes at play within the soil.

Burying cotton also speaks to the urgent need to unearth the complex, multi-layered histories of this industry and to reveal troubling legacies that have been hidden from sight.

The soundscape accompanying the textile pieces was created by ZOIR from recordings made across Greater Manchester.

The piece journeys through sounds collected from the natural environment and industrial machinery at each of the six sites.

Cotton pieces 1-3: The Manchester Ship Canal and the Pomona Docks

Building the ‘Big Ditch’, as it was called, to bring ocean-going cargo ships straight to the doors of the mills in Manchester was one of the most ambitious civil engineering projects in Victorian Britain.

The Manchester Ship Canal, stretching over 36 miles straight across Cheshire, transformed both the environmental and economic landscape of the region.

From its opening in 1894, the Ship Canal was a source of great pride for the city.

It was endlessly promoted as a sign of the industriousness and sheer ingenuity of ‘Manchester men’.

It was planned in the 1880s as a way to revive the textile trade at a time when Manchester’s economy was seen to be stagnating.

After the unprecedented burst of industrial growth in the first half of the nineteenth century, Manchester was losing its premier position and facing greater competition from other newly industrialising nations.

Transportation was seen as a constraint on commercial growth and in many respects, the Ship Canal idea was a protectionist venture, designed to defend Manchester’s profitable position in the textile supply chain by cheapening the routes to market.

But the scale of the challenge to physically remake Manchester as an independent maritime port was immense.

This included creating a complete set of docks in marshy undeveloped land along the River Irwell with all facilities capable of handling large cargo ships.

Most of the land was actually in Salford but they were known as the Port of Manchester!

The four Pomona docks were in Manchester itself on an island between the river and the pre-existing Bridgewater Canal.

These docks were constructed to handle smaller coastal ships and canal barges.

The steamship Pioneer, owned by the Co-operative Wholesale Society, claimed the honour of being the first vessel registered for commercial use of the new docks on 1 January 1892.

The first shipment of raw cotton, some 4,170 bales arrived from Galveston aboard the SS Finsbury on the 16 January.

While the Ship Canal carried much cotton to Manchester in its first few decades of operation, it could not stop the relentless decline in the Lancashire textile industry after the First World War.

From the 1920s onwards chief imports by volume and value were increasingly based around the new petrochemical industry rather than king cotton.

The Ship Canal saw a precipitous decline in activity from the 1970s, with the closure of the docks in Salford and subsequent large-scale regeneration as the Quays from the 1980s.

The docks at Pomona are, at present, derelict wasteland and awaiting redevelopment.

The Ship Canal project remains a symbolic artery running through the Greater Manchester region.

Text by Dr Martin Dodge, University of Manchester.

Cotton pieces 4-6: Fletcher Moss Park, Didsbury – The Shirley Institute

Fletcher Moss Park in Didsbury is opposite the Towers (1868-1872) which is considered one of the grandest of Manchester’s Victorian mansions.

Now a business park, the Towers and its four-acre surroundings housed The Shirley Institute from 1920 to 1988.

The Shirley Institute was the premises of the British Cotton Industry Research Institute, named for the daughter of major benefactor, W. Greenwood.

The Shirley Institute was a centre for scientific research, intended to support and modernise the British cotton industry.

The research was not limited to cotton, with the addition of a silk section in 1936 and later, rayon research; the Cotton Silk and Man-made Fibres Research Association was formed in 1961.

The Cottonopolis collective consider the environmental legacies of the textiles industry regionally and globally.

At Shirley, a drive to maximise the quality of cotton production led to innovative ecological research with continued relevance today.

In the 1920s to 1930s, the Botany Department of the Institute undertook a microscopic examination of the structure of cotton plants, standardising the processes and methods of measuring cotton fibres used commercially by industry.

The Chemistry Department developed analytical methods to determine the chemical constituents of cotton, whilst the Institute also pioneered the application of physics to textile testing.

Later, in the 1970s and 1980s, environmental sciences were elevated at the Shirley – whose role included monitoring and testing for noise, dust, toxic fumes and gases, asbestos, water and effluents.

Burying cotton strips in the soil to monitor how cotton was affected by microbial conditions was undertaken from the mid-twentieth century, with research intensifying from the 1960s onwards resulting in the Shirley Soil Test. This method inspired the LITMUS project to experiment with cloth burial across significant sites related to the Cottonopolis Collective research.

Text by Dr Erin Beeston, University of Manchester

Cotton pieces 7-9: Quarry Bank Mill, Cheshire

Quarry Bank is a rare surviving example of a complete early industrial community.

Built in 1784 by Samuel Greg, Quarry Bank started as a spinning mill, before undergoing several stages of expansion and eventually introducing weaving in 1836-39.

Samuel built a complete community around the mill, including workers housing in Styal Village, an Apprentice House for the child workforce, and his own family home and picturesque gardens.

Based in Wilmslow, Quarry Bank was a convenient location for Samuel Greg to capitalise on the transport links and textile centres of Manchester and Liverpool, and by 1834 he had built up one of the largest cotton enterprises in the country.

The Greg family lived on King Street in Manchester before moving to Quarry Bank to escape the hustle of the rapidly growing industrial town.

The cloth used for this exhibition was woven on the heritage textile machinery at Quarry Bank, made on-site from raw cotton sourced from Louisiana, USA.

As part of this project, pieces of cloth were buried in the fast-flowing River Bollin.

The river is at the heart of Quarry Bank, and it is the central reason Samuel Greg chose to build in this location, as water power was the only mass power source of the time.

To ensure a more consistent flow of water, the river’s natural path was manipulated altering the landscape forever.

The impact of harnessing the power of nature can be seen both historically and today in the frequency of flooding and dry periods, and the quality of the water affected by the industrialisation of not only the cotton industry but the agricultural industry which supported it.

Today Quarry Bank is run by the National Trust, and visitors can experience this complete community with demonstrations of working textile machinery, tours of the mill workers, mill owners, and apprentice houses, as well as gardens and woodland walks.

Text by Suzanne Kellett, Quarry Bank Mill, National Trust.

Cotton pieces 10-12: Queensland Road, Gorton, Manchester

As early as 1848 meetings were being held in Manchester at the Mechanics Institute exploring the potential of the new colony of Queensland, Australia, to become a location to grow ‘slave-free’ cotton.

Just over a decade later - in the wake of the Civil War and abolition of slavery in the US, and the Lancashire Cotton Famine - attention again turned to Queensland as a potential agricultural base to produce high-quality cotton.

Queensland was also identified as a potential place for emigration for individuals, families, and communities impacted by the Lancashire Cotton Famine.

Several Manchester-linked cotton companies and cooperatives were established in southern Queensland such as the Manchester Cotton Company Estate and Robert Muir Holdings/Manchester Queensland Cotton Company.

These properties around the Nerang Creek/River created the southern border of the new Queensland colony.

These Lancashire and Manchester companies and cooperatives were established on the stolen and unceded sovereign lands of the Yugambeh Nation, and the Nerang River (Ngarang) are the lands and waters of the Kombumerri people.

Yugambeh Elders past and present have been impacted by this ongoing process of colonisation and this area around Nerang which is now known as the Gold Coast “Always Was, Always Will Be, Aboriginal Land”.

The cleared lands where cotton plantations were established suffered substantially from floods. Within five years Muir’s Manchester Queensland Cotton Company was dissolved.

The original visions for a ‘slave-free’ cotton did not come to pass, and South Sea Islanders and Pacific Islander people (governed by the Masters and Servants Act) laboured on cotton and sugar plantations all across the Queensland region.

From the 1840s onwards Australia was also identified as a strong consumer market for Manchester cotton goods.

Walking through stores or supermarkets in Australia today you can still commonly find ‘Manchester’ sections filled with cotton and linen (and now poly-cotton) household goods.

Queensland Road runs off Hyde Road and alongside Gorton Park, Greater Manchester (M18).

In soil samples taken across the six locations in the LITMUS project, Queensland Road and Gorton Park had the highest levels of lead, likely due to the impact of pollution from nearby roads and former industry.

Queensland Road was chosen as a location to bury the cotton to make a direct link to this lesser-known story about Manchester’s links to the colony of Queensland.

The ‘Queensland Road’ hanging cotton strip and the objects within the ‘So-Called Queensland’ cabinet at the Litmus exhibit, reveal the role Manchester played in the southern bordering of the Queensland colony through cotton and frontier agriculture.

We hope to raise awareness across Manchester and Greater Lancashire that slavery and indentured labour linked to cotton did not end with the abolition of slavery in the United States but continued in problematic ways in colonies such as so-called Australia.

The social and environmental legacies from the establishment of cotton and other crops is still impacting unceded lands and waters across North East, North, and North West Australia to this day.

Text by Prof. Alison Browne, University of Manchester.

Cotton pieces 13-15: The Firs Environmental Research Station, Fallowfield

Based in Fallowfield in south Manchester, The Firs Environmental Research Station is the University of Manchester’s site for environmental research.

For over 100 years, the university has used this as a space to carry out experiments in plant science, ecology, and environmental science.

Before this, the site was part of the gardens of a grand house known as The Firs.

Once the home of Sir Joseph Whitworth (1803-1887), he bequeathed it to the university in 1887.

He was the designer of the Whitworth rifle, an early sniper rifle used by Confederate sharpshooters during the American Civil War.

Whitworth is believed to have had a firing range at the Firs, still reflected today in the name of Gunnery Lane, which runs along the edge of the site, and the length of greenhouses known as the Range.

Today, people use the site and its greenhouses for research questions on topics such as climate change, plants and soils, agriculture, and air pollution.

In 1923, two greenhouses onsite were devoted to the study of cotton plants, and in particular, the pests and diseases affecting cotton yields in Sudan.

This research likely carried on for a decade or more through grant funding from the Empire Cotton Growing Corporation.

The Empire Cotton Growing Corporation played a major part in the 20th-century history of British imperialism, economic power, and colonial networks.

The cotton buried at the Firs was in a historic compost heap.

This heap must have been in use for many years but had been allowed to go wild.

The heap is covered in interesting plants carried in from elsewhere in the garden, such as unusual thistles, lemon balm, and tansy.

It is home to a family of foxes, who access their den through a large clump of bamboo.

The heap developed as people added greenery from the garden as well as waste material from containers.

So digging through reveals different layers of organic material, compost, sand, grit, and gravel.

This range of different materials will create many different habitats, allowing for a diverse mix of soil invertebrates, fungi, and microbes which aid in the decomposition of the cellulose fibres of the cotton.

Text by Dr Rachel Webster, Manchester Museum.

Cotton pieces 16-18: The University of Manchester, Crawford House Roof

Owens College, the forerunner of the University of Manchester, was forged in large part from the profits of the cotton trade and its focus from the beginning was to educate the sons of mill owners and successful merchants in applied sciences to help the Lancashire textile industry thrive.

Particular strengths were in chemistry teaching and research, directly supporting the local textile dying and calico printing business and in engineering needed for machinery-making firms that had grown into an important sector in harnessing the cotton spinning industry from early in the Industrial Revolution.

The embryonic College relocated from the congested city centre and started to develop a campus on Oxford Road in the 1870s.

At the time the area around it was a desirable residential one for the middle classes with many streets of large Georgian townhouses and some more substantial villas.

Although the industrial belt around the commercial city centre was encroaching.

Mills, factories, and gas work along the nearby River Medlock and in Ardwick would have created copious amounts of noxious pollution into watercourses and the atmosphere.

Crawford House is situated on Booth Street East and the immediate area was in the late Victorian period largely residential with a school and small hospital.

After the Second World War, the University was still huddled largely in Victorian buildings rendered soot-black from decades of coal smoke but was looking to expand into the land east of Oxford Road for new modern buildings suitable for expanding range of scientific research.

By the time the growing University looked to acquire the streets around Crawford House in the 1960s the majority of the large houses had been converted into cheap hotel and bedsits for students and a range of small businesses; there were still a range of shops for local people.

Crawford House was built by the University in the mid-1970s as the second phase of an ambitious Precinct Centre that was aimed to be the retail and services hub for all higher education institutions along Oxford Road as well as people living in newly redeveloped residential estates in nearby Ardwick and Hulme.

As was popular in large-scale urban planning at that time the sequence of buildings in the Precinct Centre were connected at upper levels for pedestrian circulation, the so-called ‘streets-in-the-sky'.

The skies above the University were visibly much cleaner by then with the introduction of smoke-control legislation, pioneered in Manchester in the 1950s.

However, the new surge of particulate air pollution from cars and diesel bus exhaust that were increasingly prevalent on Oxford Road and adjacent major thoroughfares was creating invisible contamination that infused the cotton sample that was left exposed on the roof of Crawford House.

Text by Dr Martin Dodge, University of Manchester.

Making, Dyeing and Materialising Cottonopolis

Making, Dyeing and Materialising Cottonopolis is an experimental pilot project led by Dr Laura Pottinger, bringing together the Cottonopolis Collective researchers with artists in a series of creative workshops carried out across autumn 2022.

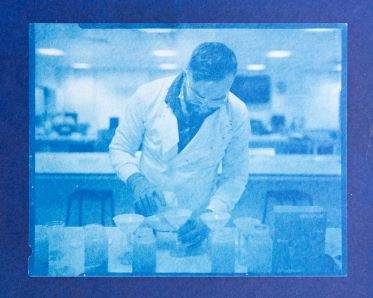

This involved site visits to rivers affected by historic textile industry pollution in Greater Manchester, and arts-based experiments in Manchester University’s Geography Laboratories.

The project aimed to stimulate interdisciplinary collaboration and discussion on the legacies of cotton.

In the sessions, artists Natalie Linney and Hayley Caine, and filmmaker Alastair Lomas joined Cottonopolis Collective researchers to explore a variety of so-called ‘natural’ dyeing techniques.

Inspired by the idea of a litmus test – a universal, dye-based indicator of pH level, derived from lichen – the idea was to examine what these colourful processes could potentially show us about the environmental impacts of the cotton industry.

With guidance from physical geographers Dr Gareth Clay and Dr Andrew Speak and support from Dr Tom Bishop and the Manchester Geography Laboratories team, samples of river sediment were analysed to understand their heavy metal content.

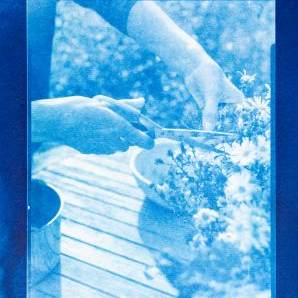

A series of playful, arts-based experiments followed, working with plant-based dyes, archival materials from Manchester Museum, and woven cotton fabric from the National Trust’s Quarry Bank Mill.

The team experimented with making anthotypes - alternative photographic images of cotton from Manchester Museum’s archives; creating eco-prints with found materials; and modifying plant-based inks and cotton swatches with metal solutions.

Each process involved working with plants and soils gathered from river locations in Greater Manchester.

These experiments raise questions about how the legacies of environmental pollution can be understood and communicated through slow, collaborative, and creative processes between scientists, social scientists, and artists.

Making, Dyeing and Materialising Cottonopolis: Environmental Legacies of Manchester’s Cotton

This short film documents the site visits, discussions, and workshops that made up the first phase of the Making, Dyeing and Materialising Cottonopolis project in autumn 2022.

It focuses on the ideas and discoveries that came about as a result of bringing expert practitioners of the physical sciences, social sciences, and arts together in a relatively unstructured environment that encouraged play, exploration, and experimentation.

Alastair Lomas is a filmmaker, photographer and ethnographic researcher undertaking a PhD in Social Anthropology with Visual Media at the University of Manchester’s Granada Centre for Visual Anthropology (GCVA).

He uses lens-based and photographic media to conduct, analyse and communicate his research, which focuses on the past, present and future relations between humans and their environment.

Alastair’s involvement in the Making, Dyeing and Materialising Cottonopolis project stems from his interest in how using materials and elements from field sites in creative processes might generate more free-form and playful conversations between research participants from different backgrounds and disciplines.

He hopes that this more relaxed approach to knowledge sharing and production comes across in the short film, which he shot during the site visits, meetings and workshops that made up the first phase of the project.

Alastair is currently based in Oban on the west coast of Scotland, where he is writing up his research into the emerging seaweed cultivation industry.

Examples of some of his photographs from this project, which were developed in locally foraged seaweed and printed in sunlight using the cyanotype method, can be found on his website.

Cottonopolis Anthotype Series

Anthotype images are created using light-sensitive materials derived from plants.

Turmeric, a plant in the ginger family, is grown commercially in India.

It is a well-known culinary spice, which can also be used as a dye for cotton fabric.

It is an ephemeral or ‘fugitive’ colour, likely to fade with wear, washing and exposure to sunlight.

This series of images, created by multi-disciplinary artist Hayley Caine, builds on experimental techniques from the Making, Dyeing and Materialising Cottonopolis workshops held in autumn 2022.

Three anthotypes – alternative photographic images - of cotton sourced from the Manchester Museum have been created using a turmeric emulsion.

The yellow turmeric stain is first painted onto cotton khadi paper and then overlaid with an image printed onto a transparent sheet.

To develop the images, they have been exposed to sunlight for six weeks, the approximate time it would take today to travel from Manchester to India via water.

Cotton photographs were taken by Erin Beeston as part of the Cottonopolis research.

Hayley Caine is a regenerative gardener, podcaster and creative researcher, working at the intersection of hyper-local colour, food and gardening.

Her work explores the temporal dimensions of growing fibre, food and dye materials.

She is particularly interested in the connections that can be made between these systems to create a regenerative future that supports plants, soil, people and microbes to flourish.

Across the different elements of her work, she sets out to cultivate a practice of mutual care, respect, and mutuality and acknowledge the entanglement of human and more than human lives.

As such, she aims to raise awareness and spark conversations on soil health and the climate emergency by reconnecting to ancestral ways of being and knowing, to help create a sustainable future of co-flourishing.

Cotton Connections

Dr Erin Beeston, University of Manchester

The Cotton Connections cabinet, curated by Dr Erin Beeston, University of Manchester, illustrates the vast international network involved in the transfer of cotton knowledge.

It also shows how Manchester traders’ desire to diversify their supply led to the spread of non-native cotton seeds across the British Empire, a form of ecological imperialism.

Seeds were sent to administrators with limited knowledge of cultivation by the Cotton Supply Association (founded in 1857) with detailed instructions and images illustrating how to grow and study cotton.

This case contains examples of cotton sent back to the Association, instructions they sent out, and evidence of correspondence with key merchants. The purpose of these experiments was to find regions within the British Empire that could cultivate cotton from New Orleans Seed thus reducing the need to import American cotton.

The term ‘Cottonopolis’ also dates to the 1850s, when Manchester’s eminence as a textile centre was well established.

Whilst these objects tell the story of mid-nineteenth-century cotton experiments, the subtext of this is Britain’s former dependence upon slave-picked cotton from American plantations.

As the American Civil War (1861-1865) loomed, cotton traders anticipated that alternative suppliers should be sought.

India was a particular focus for these efforts. In their history written in 1871, the Association stated their primary aim was: ‘nothing less than a complete revolution in the modes of cultivation… in India’.

Two images of samples grown in India can be viewed in this case.

Dr Erin Beeston, a Research Associate with the Cottonopolis project photographed objects photographed in the Manchester Museum Herbarium, which holds over 300 cotton samples.

Acquisition information is missing, though notes stored with the cotton show the samples and seeds were collected between the 1850s and 1860s.

The boxes these specimens are stored in were used under the curatorship of Grace Wrigglesworth, circa 1910-1940.

Aside from occasional inventories, these objects have been in drawers undisturbed for 100 years.

This is partly because the Herbarium was not an industry focussed collection, but rather a global encyclopedia of plants.

Newspaper titles such as the Manchester Guardian and the Cotton Factory Times were crucial to this investigation.

He is currently researching the Empire Cotton Growing Corporation which was formed in 1921 by Royal Charter to provide technical assistance to cotton growing countries within the Empire.

Through this research which uncovers details of the Cotton Supply Association’s methods of knowledge exchange, the Cottonopolis Collective has enhanced our geographical and ecological understanding of Manchester’s cotton network.

Acknowledgments

The Cottonopolis project was funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) and the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC); the Making, Dyeing, Materialising project by The University of Manchester Research Collaboration Fund; the Research Fellowship Making Slow Colour and Artist Residency in Geography by the Simon Endowment Fund.

The project has also been generously supported by the Manchester Museum, Quarry Bank Mill National Trust, the University of Manchester Geography Laboratories Teams, the University of Manchester Makerspace, the wider Cottonopolis Collective, and other colleagues at the University of Manchester.

With thanks to Abi Stone, Aditya Ramesh, Alastair Lomas, Alisha Quinn, Alison Browne, Andy Speak, Anke Bernau, Arianna Tozzi, Aurora Fredriksen, Benedict Gretton, Chris Jackson, David Browne, David Polya, Dongyang Mi, Erin Beeston, Franciska de Vries, Gareth Clay, Hayley Caine, Jane Wood, Jenna Ashton, Joe Smith, John Moore, Johnny Huck, Jonathan Yarwood, Kerry Pimblott, Laura Pottinger, Laura Richards, Lindsey Loughtman, Mark Usher, Martin Dodge, Natalie Linney, Natalie Zacek, Nathaniel Millington, Polyanna da Conceição Bispo, Rachel Kenyon, Rachel Webster, Rebecca Self, Richard Bardgett, Suzanne Kellett, Tom Bishop, Xuehan Zhou, and staff from the British Textile Biennial and Queen Street Mill.